1. Novel natural language processing (NLP) strategies to promote the revitalization and preservation of low-resource languages

Introduction:

My dissertation proposes novel natural language processing (NLP) strategies to promote the revitalization and preservation of low-resource languages. Most current language models do not focus on or have difficultly with handling low-resource languages - particularly creoles. Ultimately, I shall review the current state of the vitality of an assumed low-resource language and introduce models for tackling the various complications associated with digitizing such complex languages as a creole.

Saint Lucian Kwéyòl (also known as Antillean Creole French - ACF) serves as my base creole lens I will utilize to explore select data science models, concepts, and surveys of this supposed low-resource creole language. Without first reviewing its current status, one cannot claim to have successfully aided in the revitalization or preservation of a language. However, in my research, I found a lack of definitive information on the current status of the Kwéyòl language. Thus this lack of Kwéyòl language information presented a unique opportunity to bolster my dissertation by pairing the NLP exploration of a low-resource language with an investigation of the vitality of an assumed low-resource language.

Working Title:

Novel natural language processing (NLP) strategies to promote the revitalization and preservation of low-resource creole languages through compiling, deciphering, and understanding creole data.

Working Statement of Problem:

What are the factors associated with Saint Lucian Creole’s exclusion from most modern machine translation platforms, and how can this exclusion be addressed through Data Science tools and techniques? Can the Kwéyòl language be effectively served through the exploration of the two linguistic structures of Dependency and Phrase Structure?

Draft Hypotheses:

-

Initial Hypothesis for Foundational Surveys: Since no language survey has been conducted after the 1970s only assumptions can be made about the current status of the language’s vitality. As of that time, about 90 percent of the population was believed to be capable of communicating in creole, however, the degree of fluency of several newer generations is unknown. Therefore, several survey results may approve or disprove this belief, while simultaneously bringing attention to the preservation needs of the language.

-

Hypothesis: One could fine-tune parts of speech/name tagging for a low-resource creole language using annotations from related languages (other established creole languages and other established target languages such as French, English, and Spanish). This would be achieved through a process like “Cross-lingual Multi-Level Adversarial Transfer to Enhance Low-Resource Name Tagging”.

-

Hypothesis: One could fine-tune current language detection tools and techniques since they are incapable of effectively detecting the etymology of words not present in their data bank, thus limiting the potential for the expansion of linguistic resources for low-resource languages (such as creoles). Ultimately, dimensions matrix models (customized semantic similarity multilingual models) were assumed to be more adept in exploring and identifying language similarities and etymology details, than utilizing less customizable publicly available tools and techniques, such as Google’s language detection tools paired with manual annotation. It was also expected that due to the fair degree of polysemy present, the output may bear multiple synsets.

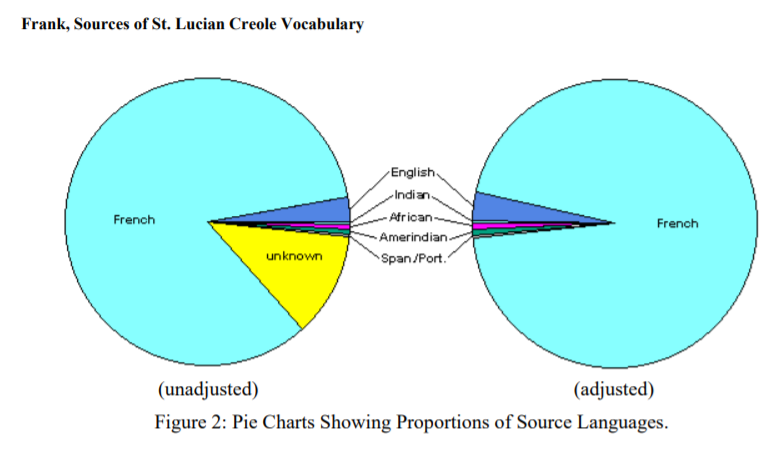

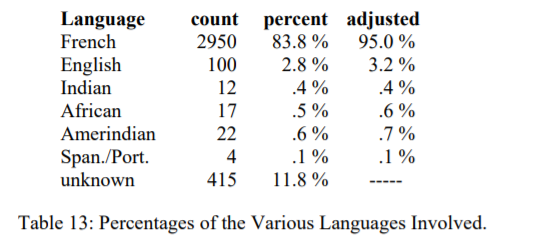

This study also sought to simultaneously approve or disprove David Frank’s hypothesis that most of the unknown Kwéyòl vocabulary is likely to have French origins. While English is the current prestige/official language of Saint Lucia, and French is the main lexifier language of “Kwéyòl, the origins of the unknown vocabulary may be from the lesser linked lexifier languages (such as arw, car, sp, Indian, and African).

-

Hypothesis: Exploring the semantic similarity of corpus related to, yet better documented than, creole (such as Haitian Creole and Guadeloupean Creole French), may assist with unsupervised statistical machine translation testing. This can be paired with a novel CNN-based semantic indexing method, and applied to multilingual data, to create semantic domain vocabulary lists. This can be used with NLP tools for enhancing language learning tools (and should ease/improve language translation outcomes on Kwéyòl data); for example, lists associated with folklore/folktales, flora, fauna, entertainment, health/emergencies, business, politics, and science where possible, can be created.

-

Hypothesis: Exploration of word phrases and word frequencies can aid in addressing issues of polysemy and word sense disambiguation in creole languages. Alpha and beta phrase parsers (Tumbling frequency parser) can reduce issues of polysemy and word sense disambiguation in ACF.

Additional papers to indicate its utility: Attempts can be made to use the phrase parser in combination with a language generator model to create new folktales based on set character entities, a moral theme, and base story samples. For example, one can Hypothesize that a good generator would be able to end stories with the typical cultural phrase “kwik kwak” and should include story characters like Konpè Lapen, Konpè Mouton, Konpè Kabwit, and Konpè Kochon.

-

Hypothesis: Facebook appears to be an online playground with increasing instances of written Kwéyòl, and vocabulary terms that may not have been captured by the current edition of the dictionary. Careful observation of social media texts can aid in building the corpus of a low-resource language, and reducing issues of polysemy and word sense disambiguation, thus improving areas such as sentiment analysis.

-

Hypothesis: The natural annotation of crowdsourced online dictionaries can be useful for building the corpus of a low-resource language, and reducing issues of polysemy and word sense disambiguation; this will be useful for building and updating vocabulary lists of current dictionaries that are not quite comprehensive. It may be useful to explore a future possibility of leveraging the natural annotation provided by crowdsourced online dictionaries related to low-resource languages, such as Wiwords.

Literature Review

Introduction and Justification of the Problem:

When exploring the matter of Multilingual Natural Language Processing, Dr. Benjamin Elson’s 1987 Linguistic Creed comes to mind (International, 2018; Ferreira et al., 2013).

“As the most uniquely human characteristic a person has, a person’s language is associated with his self-image. Interest in and appreciation of a person’s language is tantamount to interest in and appreciation of the person himself. All languages are worthy of preservation in written form by means of grammars, dictionaries, and written texts. This should be done as part of the heritage of the human race.”

In the realm of cross-lingual or multilingual natural language processing (NLP), it does appear that some languages tend to garner more attention. Typically well-established languages, with a plethora of linguistic resources to build from, often thrive while low-resource creole languages are left to languish. Creoles are a particular challenge to the NLP community as these languages tend to arise from oftentimes frantic and urgent needs to establish harmony in communication within cacophonous settings. None the less improvement in the documentation, education, and communication in these languages benefit their societies. The development of resources could enhance communication across various social statuses, improve legal and political representation, reduce miscommunications with law-enforcement figures, and increase the reach of crucial information in worse-case scenarios.

The Problematic Nature of Saint Lucian French Creole (Kwéyòl\ Patwa\Patois):

In the Caribbean, creole languages emerged as a means of survival, and endured as a result of resilience; often speakers struggled to work within the bounds of a dominant prestige language while retaining unique traces of heritage languages or contact languages. The Caribbean has had a complicated past of trade, colonization, slavery, indentured labor, and more recently voluntary immigration. This, therefore, leads to a present setting of an actively multilingual environment, that is still dynamically changing due to evolving political and legal policies (such as Citizenship by Investment (CIP) (Bayat & El Hachem, 2020; GIS, 2017; CIP, 2020; Capital, 2020; Harvey, 2020; Visa, 2016). The resilience of this language is currently being tested with the advent of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic; it created a situation where effective and timely communication is needed, while also threatening the lives of the older, more fluent, language-keepers. Therefore, the careful creation of tools and frameworks is needed to facilitate society’s creole language needs.

A creole language is different from a pidgin as it has established language rules that have been learned as a first language for one or more generations. While most are recognized as French-based, there is an increasing academic argument to officially recognize additional unique variants of English-based creoles within those settings (instead of simply viewing them as the poor application of English) (Irvine, 2020; Irvine, 2020). Even some sample sentences of the official Kwéyòl dictionary are actually English-based creole ones, rather than standard English (Frank, 2001; Crosbie et al., 2001). Thus, settings like Saint Lucia, which had over 14 territorial wars between the British and the French, may exhibit English and French creole (Irvine, 2020; Irvine, 2020).

According to Douglas Midgett’s work on the anthropological linguistics of Saint Lucia, the island’s inhabitants have struggled in their appreciation of its heritage language (Midgett, 1970). Historically there were negative connotations with Saint Lucian Kwéyòl (Antillean Creole/Patios), and upon emancipation, there was intense enmity among English and Creole in the newly free community; the use was negatively equated “with all that is backward, rural, Negro, and unsophisticated” (Midgett, 1970). Midgett highlighted that the formal teaching of Patois would be viewed as “unjustifiable and in any case, would never be tolerated by even its most ardent user”.

Ultimately, Midgett did, however, acknowledge that “English is the language of all national institutions… Patois is the language of folk institutions”; therefore, it is not surprising that some are still encouraged to learn and converse in English, rather than in Saint Lucian Kwéyòl, to appear more professional or polished (OAS, 2018). At the time, he noted that most people agreed that increased proficiency in spoken and written English (or French) would be an educational must, however, writers and other academics and actual educators had differing views; the former group believed that the use of creole in schools could aid with recognizing English as a second language, whereas educators adamantly argued against any use of Creoles in the schools.

He believed that the use of Patois in the schools interchangeably with less formal, more colloquial English would aid in establishing English in the minds of students as a functional Patois equivalent. He suggested that as long as educational institutions reinforce the conventional traditional opinion of separating the two languages, the campaign for English literacy and spoken usage will not have widespread effectiveness. Midgett, however, underestimated how pervasive the English language would be; in fact, it is the creole language that currently lacks proper literacy among the public (Midgett, 1970).

Nonetheless, as of May 1970, Midgett optimistically suggested that the vitality of the language may yet endure; he stated that “there still exists a situation in which virtually every native-born St. Lucian can speak Patois” (Midgett, 1970). Today the language still appears to exist albeit under an inconclusive status; despite the recent surge in appeal due to governmental and pop culture support, the lingering lack of definitive vitality data could inadvertently permit an unabated decline (Marmion et al., 2014; Midgett, 1970; Kabir, 2020).

In 1998, Frank explored and even expanded the written form of the creole language in Saint Lucia while attempting to effectively translate an English bible into the local language. Upon concluding his tasks he remarked that the bible would indirectly boost creole literacy through the motivational passages of the bible:

‘… for all practical purposes Creole remains an unwritten language for the majority of the population, which remains unaware of the books published in Creole. Attempts to teach Creole literacy have not met with much success because of lack of interest. Motivation is the most important factor in the success of any literacy program, and having something people want to read is the most important motivating factor’ (Frank & Frank, 1998).

English is currently the main language spoken (a prestige language) in Saint Lucia, however, Saint Lucian Kwéyòl (Antillean Creole/ Patios/ Patwa) is the heritage language of the island. There are several other languages officially taught (French and Spanish) and generally spoken in the close-knit Caribbean (such as Dutch, Portuguese, Hindi, Arabic, and even Japanese, Mandarin and increasingly Russian) (Hillman & D’Agostino, 2009; “Saint Lucia,” n.d.; Kobayashi, 2020; Nesheim, 2020; CBF, 2020).

It is this very discordant origin and complexity of structure that presents issues to the preservation of creole languages. For example, the Saint Lucian French creole writing system is phonemically-based (Frank, 2001; Crosbie et al., 2001), therefore, this makes writing the language and establishing a uniform spelling of words challenging. The language is typically orally passed on, therefore the writing system may be challenging to those unfamiliar with the recently established writing system.

Moreover, the current state of creole’s language vitality is unknown as no survey has been conducted within the 21st century. Additionally, most words in Saint Lucian Kwéyòl/creole focus on emotions, the weather, and other aspects of the immediate natural environment, including endemic animals and food sources (Frank, 2007). Therefore, finding domain-equivalent literature sources outside of certain contexts can be challenging.

Frank’s 2008 work on “Sources of St. Lucian Creole Vocabulary” suggested that just over 83% of vocabulary words he came across had French origins, roughly 3% had English origins, and Amerindian, African, East Indian sources account for about a ½ % of the total each, and .1 % was Spanish/Portuguese-based (Frank, 2007). Even this author of the official creole dictionary acknowledged gaps in its vocabulary being due to the lack of official etymological details of nearly 12 % of documented words (Crosbie et al., 2001; Frank, 2007).

Despite the advantage of cross-referencing parallel language data sources, the language challenges are made more complex by many of the vocabulary words lacking details on their origins. Ultimately, the situation could be described as bearing a “Mondrian-like” language setting. This image seems apt to explain this low-resource creole being close to parallel and monolingual data with high-resource languages (like French and English), yet the present language data may belong to different domains (Ranzato, 2020). Addressing this etymological mystery might be an apt challenge for natural language processing and machine translation.

Moreover, there are challenges present in natural language processing, particularly when dealing with sentiment analysis, word-sense disambiguation, and issues with dependency parsers in cross-lingual settings. Bearing this in mind, it may also be useful to leverage the natural annotation provided by crowdsourced online dictionaries related to low-resource languages, such as Wiwords. For example, this could actively/continuously address word sense disambiguation issues that arise from the text analysis of Saint Lucian Kwéyòl’s online social media chatter on various platforms, like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, etc. By improving word sense disambiguation issues with the creole language, one may be better able to evaluate the language’s vitality via assessing the frequency of its usage in social media posts.

For example, avocado translates to zabòka2 in the official Saint Lucian Kwéyòl dictionary. However, on Instagram3, Facebook4, and Twitter5 (and even a book on Amazon, refers to the same item using the spelling ‘zaboca’, ‘zabocca’ 67, and ‘zaboka’8. Yet, the crowdsourced online dictionary Wiwords notes the same item with the spelling ‘zaboca’9 and includes pictures for clarification.

A cursory search of Twitter revealed that the ‘zaboca’ spelling was just about as common as ‘ zaboka’, yet the accented spelling, ‘zabòka’, was not present. One could say that Wiwords did indeed reflect the term’s typical informal (social media) form. While Wiwords does not list the official spelling or all other alternative spellings, it does assist with understanding instances of the presence or absence of diacritical marks and providing needed context to improving the word sense disambiguation.

A major challenge of lexical semantics is creating training data and algorithms that facilitate downstream tasks. Furthermore, it has also been said that while there is a lingering ‘bias towards contemporary Indo-European languages’, treebanks for other language families and treebanks for classical languages are on the rise (Nivre et al., 2016). Yet, there are multiple reasons to explore NLP topics on creole data. The increasing popularity of opinion-rich resources such as blogs (Joseph, 2020), shopping websites, review portals, and social media platforms (Joseph, 2020) are rapidly attracting business people, governments, and researchers alike.

Additionally, sentiment analysis often garners high interest from businesses. Effective language detection and translation models for creole may address topics on word sense disambiguation; particularly the problems polysemy poses to sentiment analysis and how that impacts machine translation in low-resource languages. Phrase-based parsing techniques may also impact the model’s accuracy(adequacy and fluency of translation).

Not much NLP research has tackled adapting its components to creole languages; however, the academic tide has been changing as of 2020 (Soto, 2020). As of late 2020, even Carnegie Mellon University and Stanford have taken steps forward with the curate course materials that could aid directly this language preservation undertaking. Multilingual NLP, low-resource NLP, low resource machine translation (Ranzato, 2020). It has been suggested that categorizing the challenges and formalizing their interpretation using Universal Dependencies may help create a Saint Lucian Kwéyòl dependency treebank, and later facilitate other needed NLP tasks (such as sentiment analysis of texts). A Saint Lucian Kwéyòl parser may be constructed by leveraging the base knowledge of French syntax. However, these may not be the only tools required to tackle the challenges of digitizing and analyzing creole languages. Therefore, it may be helpful to develop a framework to improve the models for linguistics. Perhaps an extendable framework that can demonstrate its application to low-resource creole languages.

Issues with natural annotation (challenges and solutions for annotating Saint Lucian Kwéyòl)

As noted before, Saint Lucian Kwéyòl is highly influenced by ‘imported vocabulary’; the majority of which is French followed by English, however, it should be noted that the third largest portion of the language has definitive etymological sources. These words may constitute out-of-vocabulary (OOV) regarding a standard English or French treebank and could result in difficulties for using English-trained tools on Saint Lucian Kwéyòl (Wang et al., 2020). Moreover, in terms of topic prominence, this language is regarded as a ‘Subject-Predicate-Object’ ordered language (Frank, 1992).

There may also be issues with transliteration when dealing with the etymology of words with non-Latin based characters that somewhat contribute to the creole vocabulary; this mostly would focus on target languages of Tamil and Hindi (Frank, 2007). Also, academics have suggested that despite their obvious connection, there is not always singular and direct relationships between Kwéyòl and French words (Crosbie et al., 2001; Frank & Frank, 1998). Frank highlighted that there are many cases where a Kwéyòl noun originates from a French preposition and/or article plus noun; for example, Kwéyòl’s “lavi” is related to French’s ‘la vie’, “nanj” to ‘un ange’, “zòdi” to ‘les ordures’ and “dlo” to ‘de l’eau’ (Crosbie et al., 2001; Frank & Frank, 1998).

It is also important to note that additional natural language processing issues may arise when manipulating the creole language, or attempting to adapt it to a digital environment such as a comprehensive online-dictionary. Public contributors may understand the language in terms of speaking it, however, they may not be the best teachers; that is to say that contributors may not always be clear in their explanations or contributions. Overall, straying from official spellings of words can contribute to data entry issues. For example, one can observe the accents used with “chofé” - “to heat up”, and “chofè” - a “driver” (Crosbie et al., 2001). These words without context and accents would be very difficult to decipher. Persons inaccurately applying accents, or unable to access the necessary unique characters were required (diacritics) for formal grammar can present problems in documenting the language.

As noted by Frank, some dictionary entries can present as variants of keywords, and debates can arise concerning which word should be the dominant standard form, and which should be the variant form (Crosbie et al., 2001). For example, the Saint Lucian Kwéyòl dictionary notes jòdi as the standard form of the adverb ‘today’, and hòdi as the variant form (Crosbie et al., 2001). Frank is said to address the issue of determining the Kwéyòl form of words by noting the ‘commonly-used form that is closest to the French origin (or, in some cases, origin from another source) was chosen for a full entry, and other forms less directly related to the form of the etymological source were said to be the variants’ (Crosbie et al., 2001).

Problems of polysemy in Saint Lucian Kwéyòl

Another issue with dictionary compilation in this region may deal with the overlap of meanings attributed to certain words. Polysemy is a common occurrence in the low-resource language of Saint Lucian Kwéyòl (Mayeux, 2019; Cope & Schafer, 2017). An indication of a polysemous verb in English is one that corresponds to different verbs when translated into other languages. For example, one can review the English word for ‘ask’ (for information) and ‘ask’ (for action). This can be interpreted as one word “vragen” in Dutch, however, the majority of other languages use different words for each English interpretation like “fragen” and “bitten” in German, “preguntar” and “pedir” in Spanish, and “fråg” and “bedja” in Swedish, respectively (Kreidler, 1998; Padó & Lapata, 2005).

In Saint Lucian Kwéyòl, this can be seen where the term “mwen” can signify the pronouns for ‘I, me, my, or mine’; the term “asou” is a preposition that can mean ‘on, on top of, atop, upon’, ‘ off, off of, from’, ‘toward’ or ‘about, concerning’ (Crosbie et al., 2001). The term “vè” can mean ‘glass’, ‘green’, or ‘worm’; the creole word ‘kay’ can indicate future tense as well as ‘house/, building’, ‘scale’ (appearing on the skin), and ‘reef’. “Lè” can mean ‘room’, ‘space’, and ‘time/ hour’ (including discussions of ‘when’ and ‘if’). “Tan” can represent nouns of ‘time’, ‘weather’, and an adjective indicating a ‘vague amount of something’. As a noun, “kwi” could represent the act of ‘crying/ screaming/ shouting’, as well as refer to a ‘calabash bowl or plate’; as an adjective, it could indicate the state of being ‘raw’ (Crosbie et al., 2001).

It is important to note that there may need to be considerations for word sense disambiguation issues that arise from the intermingling of an almost identical creole from the neighboring island of Dominica. Both islands appear to sound similar and some words are indeed the same, but the written form appears to vary slightly. This might be due to the liberties taken by the different authors of their dictionaries; Frank highlighted his penchant for leaning on French when considering the spelling of words (Crosbie et al., 2001). Overall, it appears that while both countries agree that the Creole writing system is phonemically-based (which can make it easier to learn than English to a certain extent) (Crosbie et al., 2001), there are slight differences in diacritic use and placement and spelling between countries; this issue can then permeate and linger in both creole speaking countries.

It is said that the shared creole alphabet writing system arose out of two creole ethnography workshops held in St. Lucia in January 1981 and September in 1982; this was developed through the efforts of researchers at “the University of the West Indies (U.W.I.), The Université Antilles – Guyane groups from St. Lucia (MOKWÉYÓL), Dominica (K.E.K.) and the Groupé d’Etude et de Recherche en Espace, Creolophone (GEREC) from Martinique and Guadeloupe” (of Dominica, 2020). Dominicans write ‘goodnight’ as ‘bon swé’, whereas Saint Lucians write ‘bonswè’ (Crosbie et al., 2001; of Dominica, 2018). Additionally, take a look at the days of the week; the words for Sunday, Monday, Tuesday, and Saturday are the same, yet, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday are different. Dominicans write Wednesday as Mèkwédi whereas Saint Lucians write it as Mékwédi, and Dominicans write Thursday as Jèdi whereas Saint Lucians write it as Jédi; the accent placement is different (of Dominica, 2018; Crosbie et al., 2001). Dominicans write Friday as Vanwédi whereas Saint Lucians write it as Vandwédi; here, while the accent is the same, the Saint Lucians appear to include an additional ‘d’, reminiscent of the original French [< Fr. vendredi] (according to Frank (Crosbie et al., 2001; of Dominica, 2018)).

Even the word, “Creole” can be viewed as a contested, polysemous term in the English language (Cope & Schafer, 2017). The term has been employed at varied periods and in several regions to distinguish a wide range of entities; this includes ‘identities, ‘languages, peoples, ethnicities, racial heritages, and cultural artifacts’ (Cope & Schafer, 2017). As an adjective, Creole was applied as an indicator of higher status bestowed upon Louisiana-born slaves to distinguish them from those born in Africa (Cope & Schafer, 2017; Brasseaux, 2005). It was also used as a noun to designate local birth in Louisiana, regardless of racial heritage; later Americans used creole when referring to people of Spanish or French descent, yet it has often been conflated with the term “Cajan” (which described French colonists that settled in Canada’s Acadia region, then migrated to Louisiana). In fact, for some time, there was also a misconception that the term only referred to whites born in Louisiana (Brasseaux, 2005).

Currently, Creole primarily refers to one’s linguistic heritage as the main source of their ethnic identity (‘often French culture and a unique Franco-linguistic dialect’) (Cope & Schafer, 2017). This is particularly true of those of mixed or ancestry foreign to the location (“Creole peoples,” 2020; Cope & Schafer, 2017). In the Caribbean, the terms ‘Creole’, ‘Kreyol’, ‘Kweyol’, or Kwéyòl can also indicate the regional creole languages such as Antillean Creole (Dominican and Saint Lucian Kwéyòl), Haitian Creole, and Jamaican Creole (“Creole peoples,” 2020; “Antillean Creole,” 2020).

Polysemy may indeed present an issue when attempting to study a language or dialects, however, these complications are in fact, often viewed positively in the cultures where creole is spoken; they are often the premise and appeal of much literature in these creole languages. Calypso, and most other endemic forms of music, may celebrate this ability to utilize words or phrases bearing double meanings to indirectly discuss topics that are often crude (Stephens, 2013). Philips suggested that Calypsos can engage this method via ‘lamina lyrics’. Much like an onion, these Calypsos have a number of different levels of meaning, concealed one underneath the other. Achieving this phenomenon, Calypsonians use frames and masks that manifest in Calypsos as a metaphor, metonym, polysemy, irony, and satire (Phillips, 2006).

My foundational works seek to create quantifiable data on the current status of the language through studying various critical members of the Saint Lucian labor force. The work of teachers, medical workers (in the realms of both physical and mental health), lawyers, and law enforcement, typically encompasses frequent interactions with people of varying backgrounds in Saint Lucia. Due to the increasingly multilingual landscape, effective communication on the island increasingly may involve applying various language skills to meet each situation. By exploring the linguistic capabilities of select professions, one may gain a better sense of a language’s recognition within society. Without such an inquiry, it may be questionable to deem a language as ‘low-resource’ if its teaching and comprehension are integral to the culture of critical community services.

These initial works would encompass data collection and the establishment of metrics on various workforce’s linguistics skills; this entails investigating what percentage of the workforce currently consider themselves fluent in Kwéyòl (or other languages) and note their frequency of utilization of their multilingual skills when interacting with civilians. Ultimately, these initial activities will focus on avoiding miscarriages of justice, education, or health, due to miscommunication, while simultaneously bolstering the vitality (and recognition) of Kwéyòl. Their purpose is to encourage the mandatory education and monitoring of the local heritage language in critical institutions. The intertwining of language education with crucial institutions would elevate Kwéyòl’s status (among the “elite”) and improve the justice system and other critical institutions.

References:

- International, S. I. L. (2018). Dr. Benjamin Elson Appointed Executive Director. In SIL International. SIL International. https://www.sil.org/history-event/dr-benjamin-elson-appointed-executive-director

- Ferreira, J.-A. S., Taitt, G., & Douglas, K. (2013). Bible Translation (s) in the Caribbean. West Indiana and Special Collections, University of the West Indies.

- Bayat, S. M., & El Hachem, H. (2020). Saint Lucia - The Corporate Immigration Review - Edition 10 - TLR. In The Law Reviews. The Law Reviews. https://thelawreviews.co.uk/edition/the-corporate-immigration-review-edition-10/1227321/st-lucia

- GIS. (2017). Chamber discusses CIP changes. In Saint Lucia - Access Government. GIS. http://www.govt.lc/news/chamber-discusses-cip-changes

- CIP, S. L. (2020). CIP FAQs. In Citizenship By Investment. cipsaintlucia.com. https://www.cipsaintlucia.com/faqs

- Capital, A. (2020). Saint Lucia Citizenship by Investment - Your 2nd Passport. In Arton Capital. Arton Capital. https://www.artoncapital.com/global-citizen-programs/saint-lucia/

- Harvey, L. G. (2020). Saint Lucia Citizenship By Investment Program (CIP): HLG. In Harvey Law Group - World’s Leading Law Firm in Business Law, Investment Immigration, Citizenship-By-Investment, Residency-By-Investment. Harvey Law Group. https://www.harveylawcorporation.com/saint-lucia/

- Visa, I. (2016). CIP Restructuring In Progress for Saint Lucia. In Qicms- Saint Lucia CIP Restructuring | Citizenship by Investment. invest-visa. https://www.invest-visa.com/Post/240231/Immigration-News/CIP-Restructuring-InProgress-for-Saint-Lucia

- Irvine, M. (2020). St. Lucia Creole English and Dominica Creole English. World Englishes. https://doi.org/0.1111/weng.12519

- Irvine, M. (2020). Language contact in St. Lucia: The features and origins of St. Lucia Creole English [PhD thesis]. ResearchSpace@ Auckland.

- Frank, D. (2001). The Kwéyòl Writing System. In Work Papers of the Summer Institute of Linguistics in St Lucia. SIL International. http://www.saintluciancreole.dbfrank.net/dictionary/spellingguide.pdf

- Crosbie, P., Frank, D., Leon, E., & Samuel, P. (2001). Kwéyòl dictionary. Castries, Government of Saint Lucia, Ministry of Education. http://www.saintluciancreole.dbfrank.net/dictionary/KweyolDictionary.pdf

- Midgett, D. (1970). Bilingualism and linguistic change in St. Lucia. Anthropological Linguistics, 158–170. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30029245?seq=1

- OAS. (2018). Organization of American States: Democracy for peace, security, and development. In OAS. Organization of Eastern Caribbean States Commission represented by St. Lucia and the Innoved Uniq, Quisqueya University, Haiti. https://www.oas.org/cotep/LibraryDetails.aspx?lang=en

- Marmion, D., Obata, K., & Troy, J. (2014). Community, identity, wellbeing: the report of the Second National Indigenous Languages Survey. Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Canberra.

- Kabir, A. J. (2020). Creolization as balancing act in the transoceanic quadrille: Choreogenesis, incorporation, memory, market. Atlantic Studies, 17(1), 135–157.

- Frank, D., & Frank, D. (1998). Lexical challenges in the St. Lucian Creole Bible translation project. Twelfth Biennial Conference of the Society for Caribbean Linguistics, Castries, St. Lucia, 1–16. https://www.saintluciancreole.org/workpapers/lexical_challenges.pdf

- Hillman, R. S., & D’Agostino, T. J. (2009). Understanding the contemporary Caribbean. Lynne Rienner Publishers BoulderLondon. https://www.rienner.com/uploads/4a48e971d622c.pdf

- Saint Lucia. In Countries and Their Cultures. https://www.everyculture.com/No-Sa/Saint-Lucia.html

- Kobayashi, T. (2020). Message from the Chief Representative. In JICA. https://www.jica.go.jp/stlucia/english/office/about/message.html

- Nesheim, C. H. (2020). The Saint Lucia Citizenship by Investment Programme. In Investment Migration Insider. Investment Migration Insider. https://www.imidaily.com/the-saint-lucia-citizenship-by-investment-programme/

- CBF. (2020). Saint Lucia Presents a New CIP-Project. In Cross Border Freedom. CBF. https://www.crossborderfreedom.com/saint-lucia-presents-a-new-cip-project/

- Frank, D. B. (2007). Sources of St. Lucian Creole Vocabulary. http://www.saintluciancreole.dbfrank.net/workpapers/sources_of_vocabulary.pdf

- Ranzato, M. A. (2020). Low Resource Machine Translation. In Facebook AI Research - NYC.

- Nivre, J., De Marneffe, M.-C., Ginter, F., Goldberg, Y., Hajic, J., Manning, C. D., McDonald, R., Petrov, S., Pyysalo, S., Silveira, N., & others. (2016). Universal dependencies v1: A multilingual treebank collection. Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’16), 1659–1666.

- Joseph, J. C. (2020). Kwéyòl Sent Lisi. In Kwéyòl Sent Lisi. https://kweyolsentlisi.weebly.com/

- Joseph, J. C. (2020). Kwéyòl Sent Lisi. In Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/kweyolsentlisi/

- Soto, W. (2020). Language Identification of Guadeloupean Creole. Groupement De Recherche Linguistique Informatique Formelle Et De Terrain (LIFT), 53. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03066031/document#page=59

- Wang, H., Yang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). From genesis to creole language: Transfer learning for singlish universal dependencies parsing and pos tagging. ACM Transactions on Asian and Low-Resource Language Information Processing (TALLIP), 19, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1145/3321128

- Frank, D. (1992). Clause versus Sentence in St. Lucian French Creole. https://www.saintluciancreole.org/workpapers/clause_versus_sentence.pdf

- Mayeux, O. (2019). Rethinking decreolization : language contact and change in Louisiana Creole. https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/handle/1810/294526

- Cope, M. R., & Schafer, M. J. (2017). Creole: a contested, polysemous term. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(15), 2653–2671. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1267375

- Kreidler, C. W. (1998). Introducing English Semantics. Routledge. https://books.google.com/books?id=QFiv5tDnI_sC

- Padó, S., & Lapata, M. (2005). Cross-lingual bootstrapping of semantic lexicons: The case of framenet. AAAI, 1087–1092. https://www.aaai.org/Papers/AAAI/2005/AAAI05-172.pdf

- of Dominica, G. (2020). A Brief History of Kwéyòl (Patwa). In The Division of Culture. gov.dm. http://divisionofculture.gov.dm/creole-languages/5-kweyol

- of Dominica, G. (2018). Kweyol Language. In A virtual Dominica. gov.dm. https://www.avirtualdominica.com/project/creole-kweyol-language/

- Brasseaux, C. A. (2005). French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana. LSU Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=XCBfDwAAQBAJ

- Creole peoples. (2020). In Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Enacademic. https://enacademic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/53856

- Antillean Creole. (2020). In Academic Dictionaries and Encyclopedias. Enacademic. https://enacademic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/614299

- Stephens, M. R. (2013). Imagining Resistance and Solidarity in the Neoliberal Age of US Imperialism, Black Feminism, and Caribbean Diaspora.

- Phillips, E. M. (2006). Recognising the Language of Calypso as “Symbolic Action” in Resolving Conflict in the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago. Caribbean Quarterly, 52(1), 53–73.